by Kenneth Lyen

Definition of Dyslexia

The International Dyslexia Association defines dyslexia as a condition marked by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities (1). It is the commonest neurodevelopmental disorder.

Dyslexia is a lifelong condition characterised by difficulties in reading, spelling and writing. It is a problem of understanding and working with language. Because reading and writing forms a major component of our educational system, children who are slow in learning to read are often labelled as having a learning disability. Dyslexics often jumble up their letters and have difficulty associating a sound with a letter, such that even familiar words are difficult to read. There is quite a wide spectrum of dyslexia, ranging from mild to severe difficulties in reading, listening to words, spelling and writing. Dyslexia is not linked to intelligence, but difficulty reading instructions can affect the intelligence testing.

Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition DSM-V) (2)

There is another condition with symptoms that overlap with dyslexia, but is now considered a separate entity. Known as Developmental Language Disorder (DLD), these children have no, or hardly any problems recognising words, but they cannot understand their meaning. DLD was previously known as Specific Language Impairment (SLI). Originally it was thought that DLD was part of dyslexia, but a less severe form, appearing in slightly older children.

The difference between these two conditions, is that the main problem of dyslexics is their inability to decipher the sounds of words and connect them with the visual written words. DLD, in contrast, can hear and see the words but cannot interpret what they mean. Thus they are thought to have problems with semantics (the meaning of words), syntax (the arrangements of words and phrases), and discourse (the formal orderly expression of thoughts delivered through speech or writing). DLD is therefore considered to be a higher level of processing deficit.

Dyslexia vs Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)?

In the past, it was thought that dyslexia and DLD were part and parcel of the same language disorder. Both conditions shared a core problem underlying the learning to read, which is phonology, or the ability to accurate hear phonemes (perceptually distinct units of speech sounds). Indeed both dyslexia and DLD do share difficulties with hearing these speech sounds. However, dyslexia was thought to be more severely affected in this area, and it was confirmed by testing using non-word sounds that the subject had to repeat. Dyslexics had greater difficulty repeating these sounds, and because they were unable to distinguish these phonemes, they would therefore have difficulty connecting sounds to the written language. And hence they would have difficulties reading and writing as a result.

In contrast, DLD individuals usually have less problems with phonology, and their predominant disability is in the comprehension of spoken or written language. To put it another way, their difficulty is in coping with broader oral language skills, including vocabulary and grammar, which are components of reading comprehension. Because learning to read tends to be later than learning to talk, DLD tends to be diagnosed later, when the children attend nursery class or kindergarten.

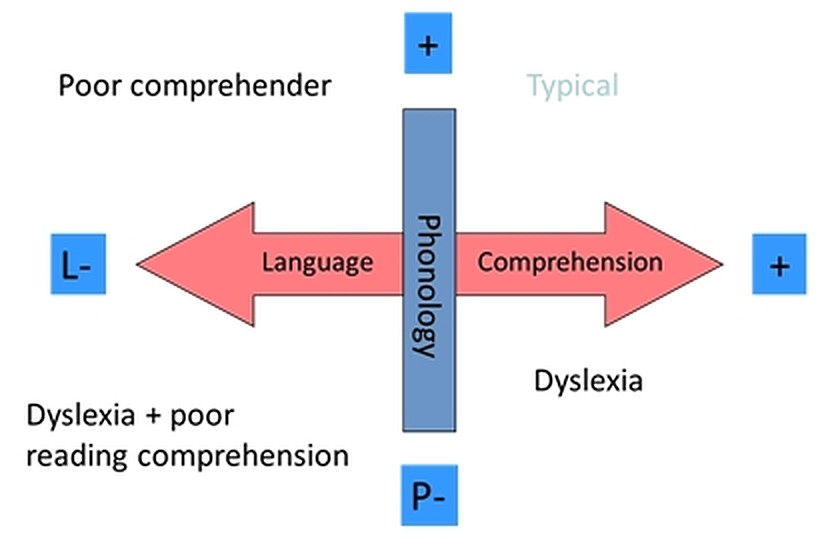

The distinction between dyslexia and DLD is depicted by the two-dimension model of Bishop and Snowling (3):

In the diagram above, dyslexics are shown lower down the phonology vertical, while DLD (“poor comprehenders”) are shown horizontally on the left of the language comprehension spectrum. The bottom left quadrant are the combined dyslexics with poor listening skills, and DLD with poor reading comprehension.

Recent studies have shown that dyslexia and DLD are indeed two distinct separate entities, but they frequently share comorbid impairments.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of dyslexia ranges from 7% to 15%, with an average of about 10%, while the prevalence of DMD is slightly lower at 7% (4). Dyslexia is the commonest learning problem.

Epidemiological studies (5) show a male predominance ranging from 1.5:1 to 3.3:1. There have been some comments that perhaps females are underdiagnosed because they are less frequently referred to diagnosticians. The reason why males are more frequently finger-pointed and referred, is because dyslexic males tend to have more unruly behaviour and express their frustrations more physically in class. This male-female inequality is still being studied and debated.

Early Diagnosis (6)

It is unusual to diagnose dyslexia under the age of 1 year. Most children are diagnosed after the age of 2 years. One suspects the diagnosis when the child learns new words slowly, takes longer learning how to speak, finds rhyming challenging, are unable to distinguish between different word sounds, reversing sounds in words, or confusing words that sound alike. At nursery school or kindergarten they may display difficulty spelling, avoid activities that involve reading, spend a long time to complete reading or writing-related tasks, read below the level expected of their age, have difficulty copying from a book or a board, have difficulty remembering or understanding what they hear, are unable to pronounce unfamiliar words, or have difficulty finding words to express their thoughts.

Let’s step back for a moment. Any child who is slow with language development must first have their hearing checked. It would be sad to miss the diagnosis of hearing impairment, as the treatment is totally different from that of dyslexia.

The British Dyslexia Association lists the following early signs that should raise your suspicion of the diagnosis of dyslexia (7):

- Difficulty learning nursery rhymes

- Difficulty paying attention, sitting still, listening to stories

- Likes listening to stories but shows no interest in letters or words

- Difficulty learning to sing or recite the alphabet

- A history of slow speech development

- Muddles words e.g. cubumber, flutterby

- Difficulty keeping simple rhythm

- Finds it hard to carry out two or more instructions at one time, (e.g. put the toys in the box, then put it on the shelf) but is fine if tasks are presented in smaller units

- Forgets names of friends, teacher, colours etc.

- Poor auditory discrimination

- Confusion between directional words e.g. up/down

- Family history of dyslexia/reading difficulties

- Difficulty with sequencing e.g. coloured beads, classroom routines

- Substitutes words e.g. “lampshade” for “lamppost”

- Appears not to be listening or paying attention

- Obvious ‘good’ and ‘bad’ days for no apparent reason

Genetic Causes (8,9)

Dyslexia often runs in families, suggesting that there is a genetic component, and indeed this is by far the commonest cause. However, some people develop dyslexia after a brain injury arising from infection, trauma, or a stroke. But these “environmental” causes are relatively rare.

Deletion of the DCDC2 gene is associated with difficulty detecting certain types of visual movements (1). Mutation in the ROBO1 gene link between auditory pathway to the brain is weakened (12). These, and many more gene mutations, are believed to converge to cause dyslexia.

The importance of studying genes is that they control protein synthesis and neural connections, among its many functions. Hence further research into this area can provide further insights into the pathophysiology of dyslexia.

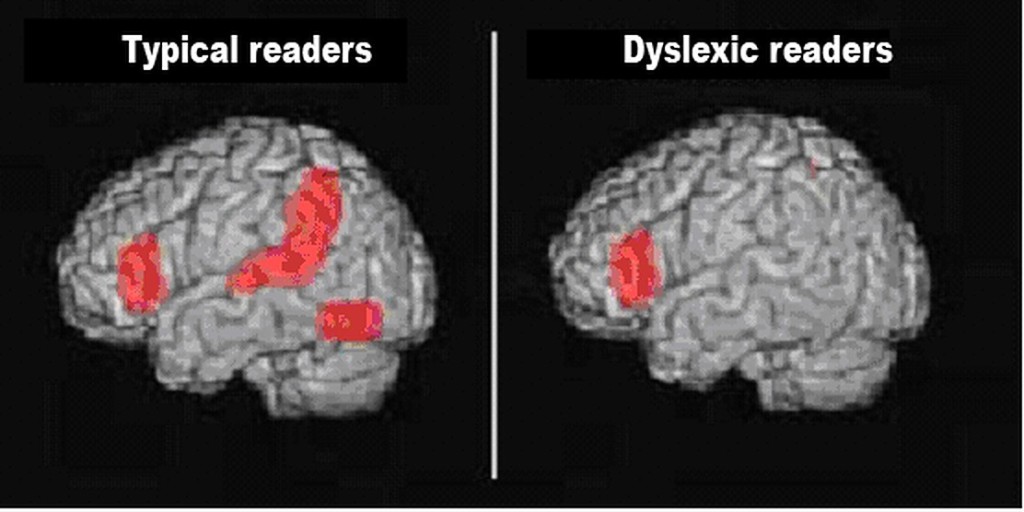

Brain Imaging Studies (12,13)

Functional MRI Scans the whole brain and shows the connectivity between different regions. Weaker connections in certain parts of the brain correlate with dyslexia. Brain imaging studies have shown that there are differences in how the dyslexic brain is structured and how it functions.

There are no problems with vision, or motor coordination. (See the references for more detailed analyses).

Controversy: Phonological Deficit Hypothesis (14)

Is dyslexia a problem of hearing, reading, or understanding language? In other words is it an auditory problem, a visual problem, or a problem of making sense of words? One of the earlier theories of dyslexia is the Phonological Deficit Hypothesis.

The basis of this hypothesis is founded on the observation that reading is a complicated process and starts with recognizing individual words and sounds. Each word can be dissected into smaller sound elements which are known as phonemes. For example the word “cat” can be broken down into 3 phonemes: “kuh”, “aah”, and “tuh”. Dyslexics have problems distinguishing the words into distinct phonemes elements. This makes it difficult for them to match specific sounds to specific letters. Difficulty distinguishing “volcano” to “tornado”. Inability to join sounds to letters results in dyslexia.

The Phonological Deficit Hypothesis has been challenged, and has currently fallen out of favour, However, it formed the basis of one of the therapies used in the management of dyslexia, the Orton-Gillingham Approach (15). This technique is to help break words down into their component sounds, match the sounds to the letters, and then blend those sounds together. This therapy employs a multi-sensory approach. For example, children might be asked to trace letters in sand, or clap out syllables in words. To date there is no convincing evidence that this technique improves dyslexia.

Problems Associated with Dyslexia (16)

Children who have dyslexia have difficulty reading and writing, and take a longer time to understand what they are taught. They tend to do poorly in spelling tests and school exams, which will lower their self-esteem., and some may even become anxious and depressed They are also at increased risk of having impulsive behaviours, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The Mayo Clinic lists the following problems if dyslexia is untreated:

- Trouble learning. Because reading is a skill basic to most other school subjects, a child with dyslexia is at a disadvantage in most classes and may have trouble keeping up with peers.

- Social problems. Left untreated, dyslexia may lead to low self-esteem, behavior problems, anxiety, aggression, and withdrawal from friends, parents and teachers.

- Problems as adults. The inability to read and comprehend can prevent a child from reaching his or her potential as the child grows up. This can have long-term educational, social and economic consequences.

Tips for Parents on How to Manage Dyslexia

1. Start reading to your child from a young age. Interest them with picture books and use emotions to represent the different characters of the story. Point to words of interest in the book. Get your child to guess what happens next in the story. Make reading an enjoyable positive experience.

2. In an older child, get them to read back parts of the story to you, gently giving corrective feedback. You can also monitor how long it takes for your child to read a short passage. Children can enjoy being timed, and they take delight in seeing if they can improve their time. Repeating the reading of a passage can improve fluency.

3. Build vocabulary. Ask your child to inform you of the new word they have learned every day. Talk about the word, its meaning, placing the word in a sentence, and checking on its meaning in a dictionary. Play word games where you try to insert the new word into a sentence at least twice that day, then again that week. Write down the daily list of new words and run through them weekly.

4. Play games. Engage your child by playing fun word games. For example, clap with each syllable of a word spoken out loud. Separate the components of a multi-syllabic word, and them join them back together. Point out alliterations (sound duplications) in songs, poems, and nursery rhymes.

5. Sing songs, learn to play music instruments. Many dyslexics display music, artistic, and other creative talents. Encourage them.

6. Go high-tech. Don’t be afraid to use computer resources, apps, digital learning games. Instruction must be explicit, motivating, systematic, and supportive. Be guided by what classroom is also teaching. But do not spend too much time on the computer at home in case your child becomes too addicted to it!

Practical Classroom Management

a) Students learn more effectively in small groups (preferably 1:3 to 1:6) but this may not always be possible to achieve in some schools. Ideally the teachers should have received training in the teaching of children on how to read.

b) Try introducing and talking around the subject matter before reading the text. Whenever possible, relate the text to real life experiences. Enhance the teaching with pictures, common household items, outdoor activities and field trips.

c) Increase vocabulary by selecting practical high-utility words. Apply the new words in conversation and in writing. Teach proper pronunciation by properly reading the words, and learn about word derivations and manipulations (roots, affixes). If the word has several meanings when used in different contexts, talk about them. Explore figures of speech, synonyms and homophones, and try to give concrete applications of these words.

d) Teach the rules of language, correct spelling and the exceptions where the rules are allowed to be broken.

e) Get the child to read texts pitched at their level. Use the same words in different contexts, and try fluency drills with repeat practising of these same words.

Bilingualism (17)

Many schools advise parents and caregivers of dyslexic children to avoid bilingual language use at home. Research evidence does not show any advantages or disadvantages of dyslexics from bilingual families. Certainly bilingualism is not a cause of dyslexia. Converting into monolingual conversations at home also shows no benefit. Some have suggested that bilingualism might even benefit dyslexics learning to read, but there is no evidence to support this claim either (17).

Different Languages and Different Countries (18,19)

What is fascinating is the comparison of the prevalence of dyslexia in different countries :

Fig 1. Percentage of dyslexics according to corresponding countries (Husni, Jamaluddin 2008) (18)

However, studies like this have been subject to criticisms. The different prevalence in different countries may be due to a combination of other factors, including different cultural and socioeconomic environments.

Another comparison (20) is showing that the prevalence of dyslexia in China is 3.9%, which is lower than the prevalence in western countries, which range from 5 to 17%. But before you draw the conclusion that pictographic languages like Chinese are less likely to result in dyslexia, studies of Japanese dyslexics come to the opposite conclusion. The difference between dyslexics in hiragana, the Japanese alphabet is very low, at 1%. In contrast, the prevalence of dyslexics using the kanji pictorgram is higher at 5-6%.

Below is a mouse, used in English, and a similar-sounding word in several European languages. The captions under the picture show how other languages write the equivalent of mouse in their own native writing. There must be a range of difficulty in reading and writing these different languages. Researching the mechanisms of language learning is important in getting into the fundamental understanding of brain function. Another area of suggested research is to see how different languages can affect the behaviours and personalities of the native speakers. And another area of research is to compare computer language with human language, and how artificial intelligence can merge the two together.

New Technology (21)

There are many new ways to help dyslexics, and the number of new devices and programs are increasing. Here are some that are currently available.

1 Dragon Naturally Speaking transcribes spoken into written words, and translate the words into other languages.

2 Natural Reader is the opposite of Dragon Naturally Speaking, in that it converts the written text into speech. It also has an inbuilt translator so that the speech can be delivered in another language.

3 Livescribe Smart Pen facilitates writing on a computer, and has other functions including audio recording.

4 New fonts with alphabets designed to be heavier at the bottom, so as to prevent readers turning the alphabet upside down.

5 Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) can observe in real time which areas of the brain are used in speech and reading. This enables one to diagnose dyslexia, as well as to assess which therapy is most effective in training the dyslexic brain to speak, read and write.

Early History of Dyslexia (22)

Doctors and medical students will remember the name Adolph Kussmaul, who described the slow sighing breathing in diabetic ketoacidosis, and is now known as Kussmaul respiration. In 1877 he coined the term “word-blindness” to describe patients who had difficulty reading. Ten years later, in 1887, a German ophthalmologist, Rudolf Berlin, first used the term “dyslexia” to describe the patients who despite having good eyesight, was unable to read the written words. In 1896, the British physician first identified the condition in a child, and describedthe symptoms of dyslexia in greater detail.

Famous Dyslexics (23)

The list of famous dyslexics is very long. We suspect, but cannot prove whether those famous people who are no longer with us, really did have dyslexia. But we do have some reasons why we think Leonardo da Vinci had dyslexia. Although none of these findings are diagnostic by themselves, the combination leads one to think he was dyslexic. He drew and wrote with his left hand, he was able to write mirror image effortlessly (a feature of many dyslexics), and he frequently made spelling mistakes especially in homophonic words.

It is also interesting to note that 35% of entrepreneurs are dyslexic, compared to 10% of the general population. These dyslexic entrepreneurs appear to be good at creating new ideas, they are often good at speaking and delegating tasks.

The question all of us are asking is why so many world-famous brilliant people dyslexic? One would have thought that the inability to read and write fluently must be a handicap. So why have so many people accomplished such incredible strokes of genius?

One popular theory is that if you are handicapped in one area, you will overcome the difficulty by finding another area to excel in. For example, the blind can hear sounds and touch objects more sensitively, and the deaf and see more clearly. What seems quite counter-intuitive are the famous writers, some of them confessing that they do suffer from dyslexia.

Conclusions

Dyslexia is a common condition affecting around 10% of the general population. Early recognition can help the affected person become more fluent in reading, writing and understanding language. This will have psychological benefits. Researching into the mechanisms of dyslexia, an the different forms it takes in different languages and cultures can help deepen one’s understanding of how we acquire knowledge and communicate with one another. Hopefully we will gain insights into how we think, and how we develop our personality.

References

1 International Dyslexia Association. Definition of Dyslexia.

https://dyslexiaida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/

2 Catts HW et al. Are Specific Language Impairment and Dyslexia Distinct Disorders?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2853030/

3 Snowling M. Dyslexia and developmental language disorder: same or different?

https://www.acamh.org/blog/dyslexia-developmental-language-disorder-different/

4 Laasonen M et al. Understanding developmental language disorder

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5963016/

5 Arnett AB et al. Explaining the Sex Difference in Dyslexia

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5438271/

6 Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity. Suspect dyslexia? Act early.

https://dyslexia.yale.edu/resources/parents/what-parents-can-do/suspect-dyslexia-act-early/

7 British Dyslexia Association. Signs of dyslexia, early years.

https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/children/is-my-child-dyslexic/signs-of-dyslexia-early-years

8 Hensler BS et al. Behavioral Genetic Approach to the Study of Dyslexia.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2952936/

9 Schumacher J et al. Genetics of dyslexia: the evolving landscape.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2597981a

10 Chen Y et al. DCDC2 gene polymorphisms are associated with developmental dyslexia in Chinese Uyghur children.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5361510/

11 Hannula-Juppi K et al. The Axon Guidance Receptor Gene ROBO1 Is a Candidate Gene for Developmental Dyslexia.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1270007/

12 International Dyslexia Association. Dyslexia and the brain.

13 Elnakib A et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings for dyslexia.

14 Wikipedia. Phonological deficit hypothesis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phonological_deficit_hypothesis

15 Wikipedia. Orton-Gillingham.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orton-Gillingham

16 Mayo Clinic. Dyslexia

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dyslexia/symptoms-causes/syc-20353552#

17 Rosen P. FAQs about bilingualism and dyslexia.

https://www.understood.org/en/learning-thinking-differences/child-learning-disabilities/dyslexia/faqs-about-bilingualism-and-dyslexia

18 Husni H, Jamaluddin Z. A retrospective and future look at speech recognition applications in assisting children with reading disabilities.

Click to access Husniza_husni_WCECS2008_pp555-558.pdf

19 Butterworth B, Tang J. Dyslexia has a language barrier.

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2004/sep/23/research.highereducation2

20 Sun Z et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of dyslexic children in a middle-sized city of China.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0056688

21 Nixon G. How technology Is changing treatments for dyslexia.

https://www.gemmlearning.com/blog/dyslexia/technology-is-changing-treatments-for-dyslexia/

22. The history of dyslexia.

https://dyslexiahistory.web.ox.ac.uk/brief-history-dyslexia

23. List of dyslexic achievers.

https://www.dyslexia.com/about-dyslexia/dyslexic-achievers/all-achiever

Written by Kenneth Lyen

22 June 2021

You must be logged in to post a comment.